Executive reporting is the lifeblood of boards, but it often hinders rather than helps. Simply put, too many boards are asked to work with far too much of the wrong material. The blame for this rests squarely with boards themselves. It is their responsibility to specify the information they require and in what form.

Getting this wrong imposes significant costs on organisations, particularly in the time and management effort to produce reports that, despite best intentions, are of little relevance or help to the governance function. Management time is wasted, and—as directors have a legal obligation to be aware of and understand the implications of what is provided to them—they must review all the material provided. They cannot afford to miss any snippets of value that might be found.

Indirect costs also include the less visible consequences of role and accountability confusion. One inherent risk is that boards are drawn into working in rather than on the business. Too much time and attention is spent on past operational activity instead of on setting expectations and evaluating the impact of that effort.

Here are some common reporting shortcomings and initiatives boards and senior management might take to improve the situation.

The perspective problem: reporting to the board is insufficiently oriented to the future

A common criticism of directors is that the material they receive is overly historical. As Charles Dickens opined (via David Copperfield): “It is vain to recall the past unless it works some influence on the present”.

Checking how the company has performed against expectations is a valid aspect of a board’s role. Looking back to learn from experience is also an important part of the job.

The board’s primary role, however, is to give direction to the business: to ensure it achieves what it should and avoids situations and circumstances that may compromise this. A board must also face the fundamental reality that it can only influence what has not yet happened. Undue reliance on the view in the rear-vision mirror is not commensurate with good governance.

So, boards need more future-facing information that stimulates and informs conversations about where the organisation is heading and a range of possible futures. The sort of information that will help it explore the current and prospective operating environment (including the behaviour of competitors) and the changing incidence and profile of risks facing the business that might affect its preferred strategies. Boards need to understand and question management thinking about their assumptions and intended future actions in pursuit of board-defined outcomes.

Rather than relying on ‘lagging’ indicators that describe what has already happened, boards needs to define and track the ‘leading’ indicators that are the primary levers for improving business performance and that motivate and provide ‘pull along’ momentum for change. [1]

The focus problem: reporting does not focus on implementing the strategic plan

Directors frequently say they spend a lot of time on developing a strategic plan, then do not get management reports against it. That is not surprising, given the inherent weaknesses of most strategic plans as governance tools. [2] Predictably, the main content of reporting describes management activity (ie, what management has been doing) rather than the impact of their effort on the business (ie, what they have achieved).

Following an annual board retreat when the board is directly engaged in ‘strategic planning’, management—and even the board—often revert to business as usual.

Every board should define its performance expectations of the business, usually directed to a higher level of achievement. It is better, therefore, for a board to reframe its thinking about the strategic plan (or its equivalent) as its ‘change agenda’.

Implementing a change agenda to improve business performance requires a surprising amount of effort. Business as usual is often a comfort zone for directors—particularly if they come from a similar environment. They like to be involved and want to help. For these and other reasons, BAU exerts a significant gravitational pull.

Day-to-day business naturally consumes a great deal of available management time and energy. So, boards with non-executive directors derive much of their potential value from being somewhat removed from the day-to-day. They are then better placed to drive the implementation of their companies’ change (ie, improvement) plans.

Reporting progress against achievement of strategic priorities must be at the forefront of every board meeting. To facilitate this, the content of a strategic document relevant at the board-level [3] should be expressed in terms of intended outcomes rather than proposed activity, at least initially. Organisations continue to exist only for as long as they produce worthwhile benefits for defined stakeholders.

Although achieving desired outcomes may not always suit month-by-month reporting, this should not be an excuse for failing to keep strategic imperatives front of mind for both board and senior management.

The chief executive’s report to a board is important for keeping the board future-focused, and driving and expressing accountability for achieving the strategic direction. Sadly, few chief executive reports stimulate the kind of strategic dialogue that most boards say they want. Directors do not want or need a ‘diary dump’. [4] They do want to understand how their chief executive and team have created value for the company and its shareholders. They also seek a level of comfort that, if not on track, remedial action is in hand.

Chief executives frequently report problems in preparing their reports to the board. Typically, they do not receive reports from their teams in time to review them before they go directly into the board pack. Boards have a right to expect any executive reporting to the board to be ‘owned’ by the chief executive. The timing of the reporting cycle should allow for proper review by the chief executive.

Even then, a chief executive’s report creates far less value for the board if it is just a summary of other executive reports in the board pack. The chief executive, as the head of the company, should be able to synthesise—with the strategic plan or equivalent document plan as the reference point—all the key factors relevant to current and prospective performance, which the board should also be aware of and thinking about.

Of all the management-generated reports going to the board, the chief executive’s report should be the least operational. It should set the scene, providing context for the board meeting dialogue. It should also be the report directors want to read first, and that delivers the greatest value to them in their thinking about the meeting ahead. Routine operational reporting should be an appendix at best and, ideally, listed as a separate ‘for noting’ agenda item—more for background information than anything else.

The quantity problem: the volume of material is far greater than the board needs

Ironically, moving to electronic board packs has made this long-term problem worse for many boards. The tedium and cost of physically assembling and distributing hard-copy board meeting packs had a restraining influence on board-pack size.

However, there is now little to hold the volume in check. Even when the agenda is tightly managed and board papers are kept within agreed size limits, the trend is to cross-reference and load additional material into online ‘resource centres’.

Separating the board pack and resource centre material may inadvertently expose directors to greater risk. It may signal to directors that the supplementary material is less important and needs less attention when it is simply the result of managers complying with size limits.

Directors often complain the volume and much of the content of the board meeting pack is unnecessary and inappropriate at board level, but they are partly to blame. In many organisations the volume of board material has grown over the years as directors request additional information. This usually gets built into routine reporting despite the requested information being of only passing interest.

Boards are typically too ready to indulge the curiosity of individual directors. It is too easy to instruct management to produce yet another report without considering the governance relevance and potential return on the investment of management time. A zero-based approach to management information is only rarely considered.

The problem is often the relative inexperience of senior executives in reporting at a governance level. They are uncertain what they should be reporting to the board—and why—and are not well placed to question requests for additional information. This problem is exacerbated because the natural response of managers is to over-report to avoid criticism that they are withholding ‘important’ information. This points to an important management training opportunity, and it is encouraging that more delivery options are emerging to address a situation long overdue for attention.

The quality problem: the way board reports are constructed and presented inhibits access to information

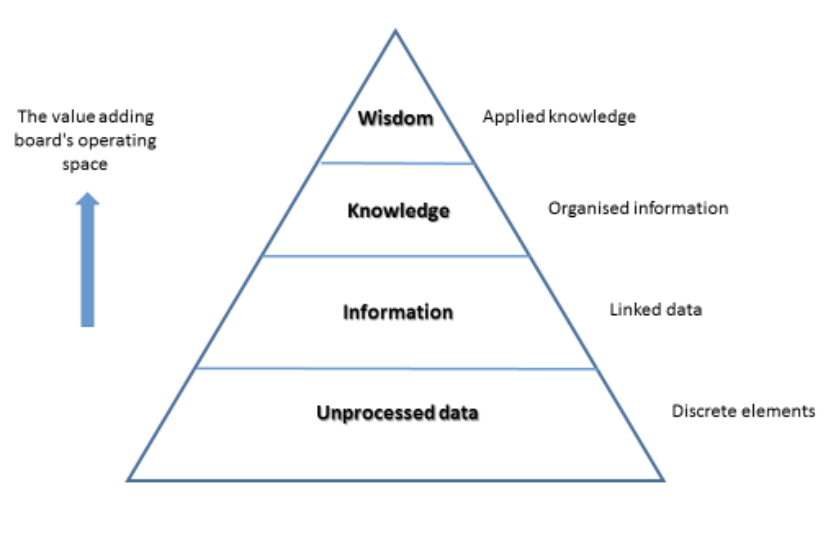

Board meeting time is far too valuable to spend working through volumes of undifferentiated and largely historical material. The following graph helps explain the problem:

Too many boards are forced to work closer to the base than the peak. Directors have little choice but to spend a great deal of time trying to interpret and interrogate what is essentially unprocessed data.

Directors should be able to spend board meeting time applying their collective judgement and wisdom to company affairs. Best-practice board reporting aims to allow boards to gain a quick appreciation of the past and present performance of the business. To get full value from their boards, organisations must aim to help them operate as far up the information pyramid as possible.

A common example of too much unprocessed data is a ‘data dump’—highly detailed tables with little or no depiction of trends, accompanying analysis, or interpretation of how they might relate to assumptions, expectations, bottom-line implications or risk management. A helpful discipline for executives preparing material for the board is to ask themselves “so what?”. Boards should expect added value from any information provided: reasoned interpretation, evidenced opinion—what does this (trend, etc) mean and is it relevant? Otherwise, what use is it to them?

These kinds of reporting shortcoming should not be blamed on management. The best boards make their expectations very clear by first determining policy parameters, performance targets and risk tolerances. Management reporting to the board can then highlight and explain variances, any remedial action, and project the consequences.

Recent extensions of that concept have included both ‘dashboard’ and ‘traffic light’ reporting structures. Both have a strong visual element that enhances understanding despite any variations in directors’ financial literacy or detailed knowledge of the business. Traffic light reporting uses colours to highlight business parameters that are meeting or exceeding expectations (green) and to draw attention to potentially unfavourable trends (orange). Red is used to highlight seriously off-track performance.

The basic premise of dashboard reporting is to provide a visual summary of performance metrics central to the overall performance of the business. It should draw attention to trends and undesirable variances, in particular, and contain a few metrics that explain the bulk of variability in business performance.

This is like the vehicle performance parameters that appear in front of a driver (speed, fuel consumption engine revolutions, etc). Easy access to such business performance information allows the ‘driver’ (or board) to to operate in a more ‘heads up’ fashion, keeping focused on ‘the road ahead’. As in a car, this information can be accessed at a glance and almost without deliberate attention or conscious thought.

The best dashboards display trend-lines and show how these relate to predetermined performance criteria (eg, a target or policy reference).

Even within companies, board reports are prepared in quite idiosyncratic styles and formats. This makes it more difficult than necessary for directors to review the board pack materials. Many boards now require formatting consistency while reporting ‘templates’ also assist the staff responsible.

The relevance problem: board reporting is not sufficiently criterion-referenced

Executive teams need to be clear what information their board requires and why. Managers often seem uncertain as to what reporting is required, not only in form but substance. They get random and inconsistent requests from individual directors, insufficiently connected to the board’s role and responsibilities. The chair should check that the wider board agrees that a request is valid and worth pursuing and not a case of wasting management’s time.

Except for the small number of decisions typically reserved to shareholders, the authority to manage the company resides with its governing board. Constitutionally, a chief executive is unable to make any decisions until his or her board delegates the necessary authority. Because of the delegation sequence—from board to management—the board must act first. This is about putting in place a policy framework that gives direction. This then delegates authority (usually to the chief executive) to interpret that direction and convert it into action to produce desired results and manage risks in a way that matches the board’s risk appetite.

A policy vacuum creates two conditions: either the chief executive is entitled to exercise free will and independent judgement, or he/she is expected to keep coming back to the board to ask for permission to act.

Another way of thinking about this is that boards have collective, full-time accountability for real-time company performance, but they come together only occasionally and for short periods of time. Because boards are physically ‘in session’ for less than 1% of the time in a year but accountable 100% of the time, they must direct the organisation they are responsible for by some form of ‘remote control’.

By establishing a policy framework, preceded by a statement of strategic intent or strategic direction, the board describes what is important to it and, therefore, what information it requires to track and evaluate performance (ie, policy compliance). For some boards, the main reporting reference point is the budget—the financial plan. For various reasons, reliance on budgeting as a planning and control mechanism has long been considered ineffective and potentially dangerous. [5]

A governance policy framework gives direction to the business, allocates decision making rights and puts the kind of constraints on management autonomy that are needed to control risk. Even when such a framework is clearly stated and visible to management, specifying the relevant strategic objective or policy reference as the starting point or context for a board paper or report is rarely consistent. It is in both board and management’s interests to use this more actively to determine relevance and materiality.

To put it another way, this is about determining the point at which the board must take an interest. For example, in reporting bad debts, when does an unpaid account become a matter of interest to the board (does it relate to size, age, debtor characteristic, or some other factor)? Does management have the authority to write off bad debts? If so, is there a point at which this decision reverts to the board?

So, if you are drifting off at p. 650 of material that seems to bear little relevance to the governance function, then the board collectively has work to do making clear what information is needed and in what form.

Notes

[1] The concept of leading and lagging indicators was first highlighted in early publications on the ‘balanced scorecard’ concept. A publication that addresses the challenges in executing strategy has a useful explanation: See Chris McChesney, Sean Covey, and Jim Huling (2016) The 4 Disciplines of Execution: Achieving Your Wildly Important Goals. The Free Press (reprint edition).

[2] As we have commented elsewhere, few strategic plans have great value at the board level. For the purposes of this article, however, we acknowledge that such plans are a significant (if nominal) focus of most boards.

[3] With a short ‘statement of strategic intent’ or similar expressing the board’s expectations, management can then plan how to achieve those expectations.

[4] That is, a description of where their time has gone since the last board meeting.

[5] See Jeremy Hope and Robin Fraser (2003). Beyond Budgeting: How Managers Can Break Free of the Annual Performance Trap. Boston, Harvard Business Review Press. A quick introduction to the basic concepts can be found at https://hbr.org/2003/02/who-needs-budgets