Common threads

Comparing Indigenous people across different countries, cultures, heritage, legal, political environments and economies shows up common threads. Ngāi Tahu’s aim in participating in this trip was to create an international family of learners to share knowledge and build Indigenous institutions and economic power.

New Zealand and Canada are similar in many ways—both first-world countries with high standards of living, a Western liberal democracy and a legal system fixed in English law. Both countries have capitalist economies, are mainly English-speaking, with populations notably dominated by immigrants who have displaced the Indigenous people, forcing them to the bottom of the socioeconomic hierarchy in just a few years.

Previous eras of failed government policy have not solved Indigenous communities’ significant issues. The original policies of colonial settler governments were generally alienation, followed by assimilation, then devolution, and now the modest but growing successes of the Indigenous self-determination agenda or, as it is known here, rangatiratanga. At its core, self-determination is the right to make their own decisions to determine their future within traditional structures.

Along with the shift in government policy comes increased accountability, as Indigenous people look to their leadership to address problems that successive governments have been unwilling, unable or incapable of solving.

Indigenous people are not looking for a replica government but their own structures to replace outside agencies, while still relying on government funds.

This is when the economies of Indigenous people need to be at a scale to support self-determination. Only then can leaders make decisions that are independent and in the best interests of the people they serve.

First Nations

According to Statistics Canada, 633 First Nations communities are dispersed through 10 provinces, comprising only five percent of the population. In New Zealand, the percentage of Māori in the population is 17.4—more than three times Canada’s Indigenous population.

Compared to the general population, First Nations people are well below national averages in all indicators, much like New Zealand. About 44 percent live off-reservation, with greater access to resources and opportunities including employment, health and education. They are consequently more affluent than those living on the reservations.

The modern-day realisation of self-determination through self-governance started with Chief Clarence Jules in 1966 and was followed by success with the Federal Government in 1988, with the Provincial Government in 1990, and implementation in 1991. By 2005, the First Nations Fiscal Management Act (FMA) resulted in the removal of reliance on Government funds in many ‘bands’ [2] or tribal authorities.

This occurred during a decade-long research project on how First Nations could develop their land and expand their economies. In 2008, Chief Manny Jules— son of Chief Clarence Jules and known as the First Nations’ Taxman—established the First Nations Tax Commission, a pan-tribal institution established under the FMA. The Tax Commission has gathered over $1B in tax revenue and developed new investments that have gone on to generate several other institutions to progress self-determination through self-governance on their land.

According to Chief Manny Jules (in a September 2020 Radio New Zealand interview with Julian Wilcox on Indigenous leaders), “The First Nations’ Tax Commission has generated over $100m per annum in tax while the Federal and Provincial governments still have jurisdiction and collected $700m per annum over that same land.”

The Commission’s role is to regulate, support and advance taxation under Section 83 of the Indian Act—so legislation that had originally destroyed any hope of an indigenous economy is now being used to advance one. The Commission renews local revenue laws, builds capacity, reconciles First Nation governance and taxpayer interests, and provides research to advance jurisdiction while separately adjudicating disputes. First Nations’ lands can tax a range of activities including agriculture, oil and gas, forestry leases, commercial leases and utilities. Tax then provides infrastructure services including roading, bridges, water and wastewater services, and park acquisitions—just like our local government.

Institutions developed to date and adding to First Nation's economic success include:

- the Tax Commission

- the Management Board (which deals with transparency and accountability)

- the Finance Authority (to access the international bond market for investment)

- the Infrastructure Institute.

The Infrastructure Institute has been designed to build on the success of the FMA model and will be optional for all First Nations, a critical characteristic for Iwi Māori. Those who choose to work with the First Nations’ Infrastructure Institute can standardise best practices to plan, procure, own and manage their infrastructure projects.

Responsible for recovering 45,000 ha of First Nations land taken under settler rule, Chief Manny Jules of the Tk’emlups Secwepemc people has honed a “focus on legislating our way back into the economy”. According to Chief Jules: “The self-determination fiscal relationship allows First Nations to take greater control over their revenues and therefore their future. It gives them a better stake in the success of their regions and allows them to take responsibility. It is consistent with best practices for the government worldwide and establishes a true nation-to-nation framework.”

Sun Rivers Resort is a premier, master-planned community five minutes from the city of Kamloops, British Columbia, where the Tk’emlups Secwepemc people are based. The development sits on a hill overlooking the twin rivers. The 900-home development has infrastructure, utilities, services and community management to a very high standard with townhouses, condos, adult-oriented homes, and a tiered golf course with resort-style facilities. The leases are paid upfront for 99 years, and common areas are beautifully maintained through a reasonable fee.

In effect, local government services are covered by the First Nations who own the land, which is administered through a federal government arrangement. A property transfer tax is applied when homes are on-sold and many of the Tk’emlups Secwepemc people live in the community.

“Both levels of government—federal and provincial—continue to view indigenous communities as a burden, so we also need to educate the mainstream population that we need to determine our future as we can look after ourselves better than anybody else,” said Chief Jules.

The governance structures in the various institutions have taken a great deal of time and energy to implement but are not considered a replica of federal or provincial government as they are run by First Nations people in their own way. The institutions must comply with federal and provincial government laws and regulations as they develop and implement their own tax-collecting and investment administrations.

Alongside the institutions, the Tulo Institute of Indigenous Economies, based at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, helps build the capacity and capability of the First Nations’ people to develop good governance practices. In August 2023, the University of Canterbury signed an agreement with Tulo to collaborate and innovate on indigenous self-determination and economic reconciliation.

Providing direction here

New Zealand’s historical, legal and institutional settings are very different from Canada, being settled in the 1840s under Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty) that supposedly gave Māori tribal autonomy and self-government.

The settler government quickly set out on a vigorous campaign—buying, appropriating and confiscating land using legislative levers that made it impossible for Māori to retain their whenua (land) as assured in the Treaty. The Native Land Court, aptly known as Te Kooti Tango Whenua, the Land Taking Court, created by the 1862 Native Lands Act, began the process of alienation that didn’t stop until the 1990s—which is why colonisation is often called the “conquest by contract”.

New Zealand, as a unitary democracy, has had no experience with Canada’s federalism, where territories within a nation-state have some level of independent self-governance. The model here has more recently evolved into co-governance and partnership between Māori structures and the national or local government as a mechanism for achieving Māori aspirations.

In the case of Ngāi Tahu, a corporate-beneficiary model was agreed as part of the Ngāi Tahu Claim Settlement Act 1998. The distributions flow from the company to the trust from which the Ngāi Tahu whānau benefit. Despite the very real need for Ngāi Tahu people to have the capability and capacity to administer tribal structures, care is needed to ensure the administration does not increasingly become the “why we are here”, with costs ballooning in proportion to the dollars distributed.

The cautionary tale for some time has been of those who deliver social programmes and iwi benefits becoming the principal beneficiaries of the business of distribution. This must be managed carefully to ensure those that need to be taken care of, are. Forward momentum will come from removing layers of bureaucracy and keeping the system lean, replacing leadership on a regular basis to ensure new ideas and strategies are given light in the fast-changing world, and educating mid-career Ngāi Tahu outside the tribe.

The Ngāi Tahu Property Wigram development—which began in 2009 on the aerodrome site with 1600 freehold residential sections, a shopping centre and industrial development—could be reimagined in a different structure, with lessons learnt from Sun Rivers in Kamloops, especially if the financial projections for the Sun River leaseholders are as favourable as current projections.

Doing business currently on Māori Reserve land is impossible because of high transaction costs. The Waimakariri Council had stopped Ngāi Tuahuriri people from building there since the 1960s—other than a few exceptions—and only through the Canterbury Emergency Act post-earthquake did the land free up. There is a case for controlling the development of infrastructure, consent process and rating on Māori Reserve land, creating real regulatory authority. What First Nations have done is remove the transaction costs to allow this to happen on their land.

Strong cultural and corporate governance has emerged as the competitive advantage for the tribes, bands, confederations, nations and iwi who have used this to bring about stronger economies by building their capital base. Through that economic capacity, they build authority and influence.

The purpose of building strong corporations is to meet the intergenerational needs of their people—in this goal tribes, bands and iwi are comparable. Rigorous and independent governance and management of the capital have been used while the emerging indigenous generations train and develop in the governance and management of their assets.

The Tulo Centre for Indigenous Economics is a concept that could provide multiple benefits in New Zealand, with legal, fiscal, property, banking and investment knowledge and expertise developed in one institution, which is Māori owned and working on Māori agendas.

A conversation on how much regulatory authority Māori have on Māori land is one worth having.

Notes

[1] A semi-annual event is run with Canada and North American Institutions by the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre (NTRC) at the University of Canterbury (UC). It is led by Dr Te Maire Tau and this year included seven Ngāi Tahu early, mid and late-career participants drawn from a wide range of sectors.

The first week was spent at the Tulo Centre of Indigenous Economics (Tulo)—based at the Thompson River University in the town of Kamloops, British Columbia—which promotes First Nations’ self-determination through economic development. A relationship agreement was signed during the week to further university collaboration. The week included lectures, dialogue, discussion, presentations and social events between Ngāi Tahu and the Tulo students and academic staff.

The second week was at Stanford’s Hoover Institution (Hoover), as part of the Hoover Project on Renewing Indigenous Economies. It comprised a week of lectures, research presentations and speaker engagements with 25 American Indian and First Nations people. The former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice is the Director of the Institution, and her warm welcome was an impressive start to the week.

[2] ‘Band’ is a term the Canadian government uses to refer to certain First Nations communities.

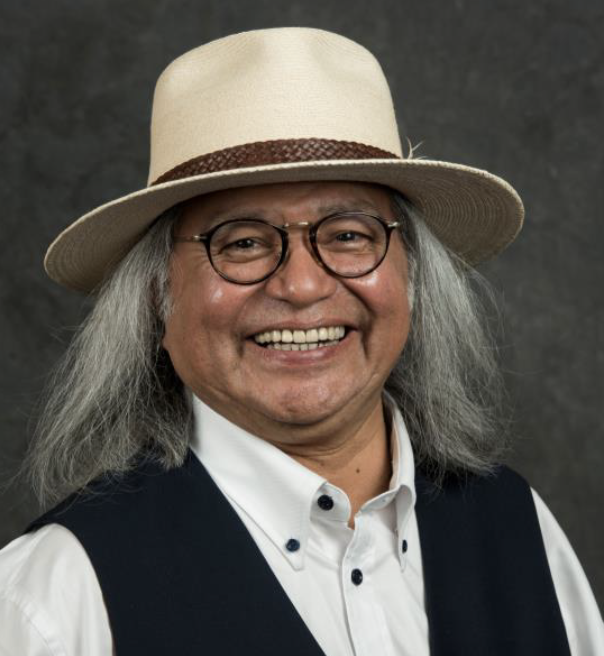

Chief Manny Jules