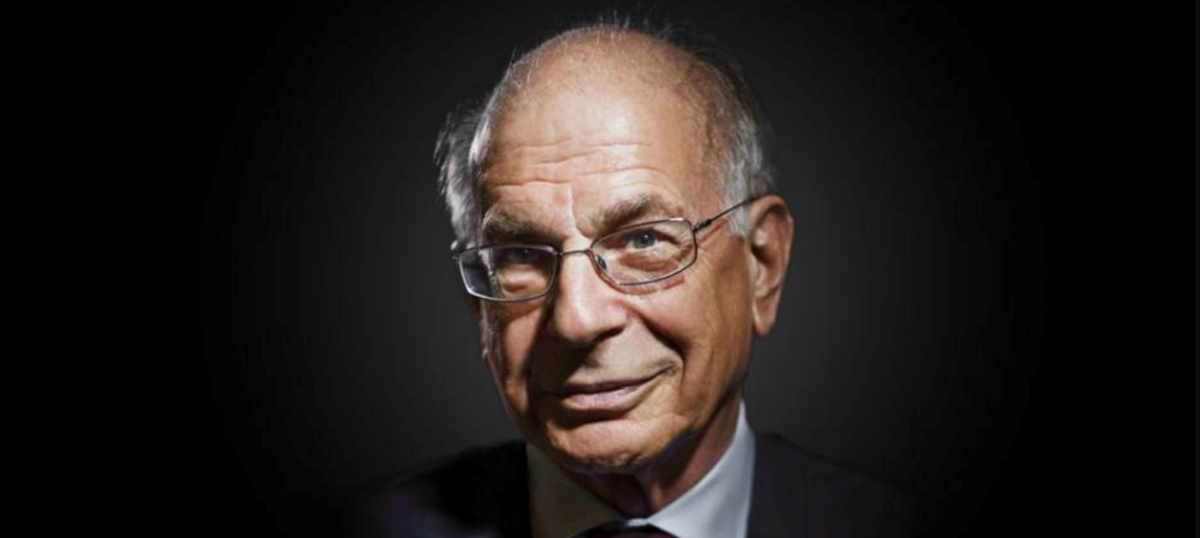

As the Washington Post obituary points out, he debunked the concept of homo-economicus—the rational being driven by self-interest. Instead, he concluded that people are essentially lazy thinkers relying on intellectual short cuts often leading to incorrect conclusions that are not in their self-interest. For this and other work he won the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in economic sciences.

In his popular 2011 book, Thinking Fast and Slow, [1] he noted that people “apparently find cognitive effort mildly unpleasant and avoid it as much as possible”. In the book he outlined the model of System 1 and System 2 thought. System 1 developed when a rapid response to perceived threats served us well. Although the days of the sabre-toothed tiger have passed, this component of our cognitive processing persists. System 2 is considered thought—and this requires work. Yet seemingly we are averse to the necessary mental effort.

Some of his early work with lifetime collaborator Adam Tversky inspired in part Richard Taler and Cass Sunstein’s concept of libertarian paternalism outlined in their book Nudge. [2] The idea being that with the right suggestions—‘nudges’—governments could direct people down desirable paths, eg, retirement savings.

He later collaborated with Sunstein and Olivier Sibony to publish in 2021, Noise: A flaw in human judgment. [3] Here they considered the variability of decision making with two central concepts: bias (a consistent skew) and noise (seemingly random variation). They note that, in the real world, the amount of noise in decisions is often ‘scandalously high’ and comment somewhat alarmingly that, “the surprises that motivated this book are the sheer magnitude of system noise and the amount of damage it does. Both of these far exceed common expectations.”

This work indeed had some sobering conclusions to share, notably that we have a rather exaggerated confidence in our own predictive judgement. In many cases, the use of simple rules, models or, increasingly, algorithms, will achieve higher degrees of accuracy. The expression of individuality in judgment detracts from accuracy. Kahneman noted that when you hear an argument passionately delivered, the only thing you know for sure is that the speaker has constructed a cogent story in their own heads—nothing else.

This is given clear evidence in the work of Justin Kruger and David Dunning, which showed those with low competence tend to overestimate their skills and the opposite is often true for high performers. When displayed graphically, the maximum separation between confidence and actual competence is given the appropriate name of Mount Stupid.

We have long been fans of Kahneman’s work, believing it to be highly relevant to the process of governance and, particularly, decision making. We suggest that a central role of a board is to make a small number of very big decisions so that others can make hundreds if not thousands of smaller decisions consistent within the direction provided. If that is so, then it is logical to pay close attention to decision processes and the influence on them.

An awareness of and conscious checking for key biases will help. We are all prone to confirmation bias, seeking information from sources that are we likely to agree with (choice of media the most obvious). Availability of information also influences perception; for example, deaths from disaster are a fraction of deaths by more common causes (asthma for instance). Inferring the general from the particular is another trap—that behaviour or traits of individuals should apply to and be representative of a broader group. We are all driven by fear of loss. If the same medical procedure is described as having either a 95% rate of success or a 5% mortality rate, the take up is radically different.

Caution around framing bias is a boardroom necessity. Outlining decisions to be made is useful but not if a chair or an influential director frames the discussion in a way that precludes consideration of all reasonable options.

Anchoring bias is something that salespeople understand. Once a number is on the table then everything else is relative to that. Try this with friends—ask them if Lake Taupo is deeper or shallower than 2,000 metres. You will get a range of answers well off the actual deepest point of 186 metres.

Hindsight bias colours the past. If a mediocre vacation ends with a great last day, you remember the whole positively—and the reverse is true. This is a far from complete list but even quietly checking for these influences will assist in better decision making.

A good director keeps an open mind to new information in a changing world. A position on any matter should be provisional—not flaky and changing at random but certainly not fixed or wedded to establish practice simply because something has persisted over time. Kahneman himself quipped that he was always delighted to be proven wrong on something because that meant he was more right about everything else. He was also asked in interview if his life’s work had made him a more rational human and replied, “Sadly, I think not”.

“Well undoubtedly there is bias in science, and there are many biases, and I certainly do not claim to be immune from them. I suffer from all of them. We tend to favour our hypotheses. We tend to believe that things are going to work, and sometimes we delude ourselves in believing our conclusions”. [4]

The lesson to learn is that we are flawed thinkers as humans and that is unlikely to change, it is part of being human. But understanding what affects our thinking may help us make better decisions. The work of Daniel Kahneman has contributed enormously to that understanding.

Notes

- Thinking, Fast and Slow. Kahneman, D. Penguin 2011.

- Nudge. Thaler, R. Sunstein, C. Penguin 2021

- Noise. Kahneman, D. Sibony, O. Sunstein, C. William Collins 2021

- Social Science Space. January 2013