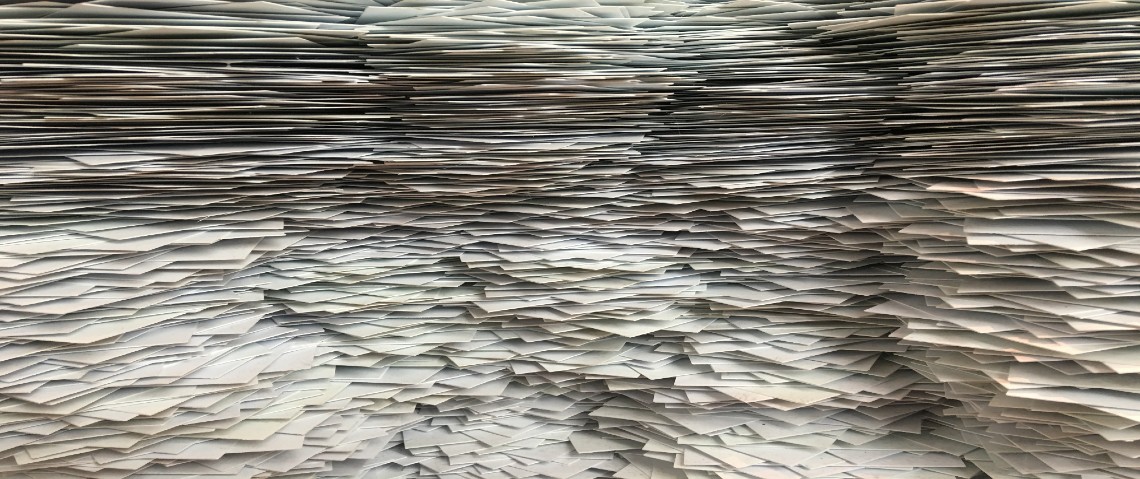

We are not, however, proposing that boards should all follow the Packer edict, nor are we proposing that it’s OK for executives to put together ‘900 pages of board papers’ and expect that their board will welcome these.

In this article we explore the design and presentation of the package of board papers so that they serve as a tool for meeting effectiveness.

The purpose of board papers

The package of paper has one very basic purpose; to provide the information necessary for an efficient and effective board meeting. They are a tool for director preparation for the meeting to come. Compliance reports — including financial reports, background reports, papers that support strategic or forward thinking, papers addressing policy matters and a report from the CEO, are the contents of a typical set or ‘pack’ of board papers. This sounds straight forward enough. And it should be; the problem is, however, that many of these papers are poorly targeted, poorly designed and not uncommonly containing information that is not governance specific. If this were not bad enough, many boards and directors accept this fact either out of ignorance of how the papers could be better presented or because the effort required to address the ‘problem’ is seen as more onerous than the effort required to make sense out of the muddled information received. Not uncommonly the CEO is left to guess what the board requires. When a board does not take charge of the design of its meeting material it is unfair to lay the blame for these problems on management’s doorstep.

Designing the ‘pack’ of papers

The ‘pack’ of papers should reflect the design of the board meeting. Ideally the papers will be packaged in a logical order that allows the meeting to flow. Most board meetings commence by addressing procedural matters, e.g. confirmation of minutes, notification of conflicts of interest etc. We advocate that the first substantive item on the agenda should be attention to matters of strategic importance or relevance. It’s good to address these while the directors’ minds are fresh and focused. This might be followed by any policy matters requiring attention. Compliance reports including financial reports should follow, then on to general business and, finally, the CEO’s report. The meeting should conclude with a brief review of the effectiveness of the meeting and a reminder of forward board issues and key matters to be addressed at the next board meeting. It follows that the order of board papers should reflect this agenda structure.

It should not be necessary to identify the writer of the paper, all papers to the board, in effect, being from the CEO. When a board exercises its role to hold the CEO to account for all operational matters, a CEO is likely to take greater care over the content and style of papers written by his or her senior staff.

Designed to assist directors to do their job

Board papers should be designed to assist directors to do their job. Sadly many are, instead, used by management as a means to engage directors in operational matters, to engage in ‘hand holding’, to describe busyness, or to purchase ‘insurance’ against insecure executive decision-making.

Papers to the board should be as brief as possible without cutting corners. We do not necessarily advocate the Kerry Packer philosophy per se, but the general principle is sound; ‘use as few words as possible to say as much as possible’. Directors should never be in the position of feeling that they have to ‘wade through mud’ in order to get to the point nor should they feel that reading the board papers is a chore. To the contrary, board papers should be read with interest and keenness in the knowledge that the information contained will facilitate a smooth, effective and blessedly short meeting. In essence, the papers should make directors’ meeting preparation as straightforward as possible.

As directors read their papers, three questions might be kept in mind:

-

How is this matter relevant to the board and to me in my role as a director?

-

What constructive use will I make of this information and is it really necessary?

-

What board document, policy or statement of strategic intent does it relate to so that I can be clear as to the context and relevance?

If, when writing board papers, management personnel kept these director questions in mind, fewer papers would be written and those that were would likely be much better targeted to their intended audience.

What shouldn’t be in the board papers?

The 900 page ‘pack’ mentioned earlier contained three classic groups of unnecessary papers and one set of ‘could be dealt with differently’ papers. In the former group were several papers asking the board to approve management actions already taken or about to be taken that were clearly within management’s delegated authority. In other words the CEO and senior managers wasted their time and that of directors by writing extensive papers asking for permission to do their job. The reason for doing so could be that there was uncertainty that their board would support the choice of operational ‘means’ or ‘methods’ that they made or were about to make. Another reason could be that, uncertain about the efficacy of their decision making, management were seeking a form of insurance protection from the board by enticing directors into the operational decision-making process thus eliminating full management accountability for the outcomes, should things go wrong. (This is a foolish strategy because even though management might argue that the board shared the decision-making, it is rare that in such circumstances that the directors are willing to share the blame or accountability for failed outcomes.)

The second group of unnecessary papers found in the ‘pack’ included a set of Powerpoint slides, the result of a presentation to management from a potential supplier bidding for the provision of a component of new product. At best these might have been of some peripheral interest to one or two directors with knowledge or background in the matter but they were utterly irrelevant to the board. We can only assume that management thought something along the following lines, “We’re embarking on a new and exciting project that we find fascinating. We think that you might be fascinated too so we have included the material that fascinated us.” In other words, “Even though you don’t ‘need to know’ this stuff, we thought it would be ‘nice for you to know’ about it.” Unless they have specifically asked for it, directors should not be presented with ‘nice to know’ information. The ‘need to know’ information is often more than directors ‘want to know’ anyway, and can amount to a considerable supply of governance-related information.

The third group of unnecessary papers included uninterpreted papers from management and from consultants and advisors. No director should be expected to plough through papers in order to find meaning or relevance. All data should be translated into information, and all information should be given a governance context and purpose.

Had management asked the three questions mentioned previously, none of these papers would have been presented and a larger number of pages of board papers would have been eliminated from the ‘pack’.

Addressing strategic issues

The board’s interest in strategic matters is paramount to its role. After all, as John Carver reminds us, the invention the future at the heart of the board’s role. But future gazing is not the board’s role alone. Management too has a keen interest in future issues. Strategic thinking is carried out at management and board levels, the latter in partnership with management. Papers addressing future issues, as is the case for all other board papers, should commence with a statement of context, for example, where does or should this matter sit in terms of the organisation’s strategic plan. Directors should be given a starting place for each paper making clear why the issue is important to the board and what outcome is sought from the resulting board dialogue. Any substantive paper should begin with a brief executive summary. Directors should also be advised of the outcome sought, be this a decision, knowledge and information in support of a decision to be taken at a later time or merely for ‘information only’. Many such papers will be designed to keep the board focused on its strategic ‘radar screen’, bringing environmental changes and issues to the attention of directors. Such papers, however, need not be held in store until the issue of board papers. Many directors that we have worked with have stated quite explicitly that they would prefer to receive a steady supply of ‘for information only’ papers either in hard copy or via email between meetings rather than a deluge mixed up with vital, decision-making reading.

Compliance reports

Our experience of boards over the twenty or more years that we have been providing governance advice is of board meeting ‘packs’ being dominated by compliance reports. Financial reports and descriptions of programme or project activity pad out an otherwise slim set of board papers. We have written many times about the need for focused, analysed and interpreted financial reports that include ‘dashboards’, graphs and narrative rather than mere data. Our ongoing experience of extensive financial data that is merely presented as series of numbers on a page convinces us of the need for widespread change in the way that financial reporting is presented. When there is a separation of ‘financial compliance reporting’ material and ‘strategic finance reporting’ material, attention to future-focused financial material does not become enmeshed or lost in the details of the historical financial figures. We regularly recommend that these two components of the financial agenda be separated and dealt with in the relevant board meeting section, i.e. compliance (historical) or strategic (future).

Compliance reporting is essential to the board meeting its duty of care, i.e. the expression of its fiduciary or stewardship responsibilities. Compliance papers will always be a core element of the board papers. Compliance reporting and related dialogue, however, should not dominate the board meeting. When compliance papers are well presented and set against board-determined criteria, directors will be able to read the ‘results’ prior to the board meeting, know whether things are ‘as they should be’ and, with good meeting leadership, move quickly through the compliance agenda, making time for attention to strategic and other forward matters. Many boards ‘package’ the compliance reports and pass them as a single agenda item. This is known as a ‘consent agenda’. Exception reporting is another mechanism used by boards to speed up the compliance oversight process.

Some organisational sectors are bound by law in respect of the reporting of certain events or circumstances. For example hospitals and certain other health services are required to report ‘sentinel incidents’, firstly to the board and then on to the relevant government agency. Other organisations are required to report certain categories of workplace accidents. Some such reports might require board dialogue, others not. Hospital boards, for example, would certainly want to discuss sentinel incidents in order to be assured that whatever conditions led to the serious consequence, e.g. death, poisoning etc, had been addressed.

Compliance reports should be the easiest for management to write. Wherever possible the board should provide the criteria against which the report writers report, making it easy for the reader to make sense of the information and data. Such reports typically require minimum narrative and lend themselves to a brief summary of the position or circumstance.

The CEO’s report

It is not uncommon to find boards constructing their board meeting around a slavish following of their CEO’s report. A common consequence of this approach is that, even though the board may wish to attend to its own matters, the CEO’s report controls the meeting content and more than likely will reflect CEO concerns.

A board should develop its meeting agenda, not abrogate this to the CEO. When a board takes control of its agenda design, a governance focus is more likely to ensue. Critical issues that the CEO needs to bring to the board’s attention should be included in the section of the meeting that the matter relates to, either policy or strategy. A paper should be written in the way we have recommended addressing the issue. This is not to suggest that there will not be matters that the CEO wishes to bring to the board’s attention or, for that matter, issues that the board feels that it wants to be kept apprised of that are neither of a policy or strategic nature. But there should be few of these. When this approach is adopted, the CEO’s report can be placed at the conclusion of the agenda. It can be taken as read and thus may require little or no comment from directors. The content of the report is ‘for information only’ and is dealt with accordingly.

The structure of the ‘pack’

When the ‘pack’ is more than, say, 30 pages, we recommend that there be a table of contents. We strongly recommend that the pages be numbered sequentially right through the full ‘pack’. The various groups of papers should follow the order of the agenda and should be separated with item tags, making it easy for directors to navigate around the various papers and reports. ‘For information only’ and supplementary papers might be grouped together at the rear of the ‘pack’. In this way, substantive or ‘need to know’ information and papers that inform board dialogue do not become lost among the less critical ‘nice to know’ material.

Summary

The design and quality of the board papers and their method of presentation are critical to a successful outcome from board meetings. Discipline is required by both directors and management to ensure that standards and requirements are clearly communicated and effectively delivered.